The State of Jordan emerged after the 1948 Arab – Israeli war. Jordan resulted from the unification of the Emirate of Trans-Jordan with the Palestinian territories in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. The 1948 war had two main consequences on the economy. First, the rapid increase in population stimulated demand for basic utilities, goods and services. Second, the foundations of economy were built through the increased intervention of the state.

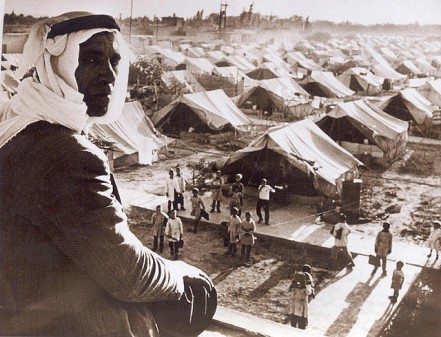

The massive inflow of Palestinians after the 1948 war brought dynamism to the economy. According to estimates, Jordan’s population tripled from 500,000 to 1.5 million in 1948-50[1]. The Palestinians brought with them their savings, together with their relatively higher education and entrepreneurial spirits[2]. This influx of financial and human capital increased demand for housing, goods and services, stimulating production. At the same time, the Palestinian entrepreneurs added dynamism to the private sector. They joined the Jordanian commercial elite in setting-up small and medium enterprises, mainly concentrated in the Amman area[3].

The government built the foundations of the economy through economic planning. Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) and economic planning inspired Jordan’s economic activity at that time. A Development Board was set up to oversee public investments under five-year plans. The first plan was adopted in 1962-7. The country’s core infrastructure of basic public utilities (i.e. water, energy, transport, and telecommunications) and public services (education and health) were built. The industrial apparatus was established according to a two-tier structure. The first tier included Jordan’s ‘Big Five’ State-Owned-Enterprises (SOEs): the Jordan Phosphate Mines Company, the Jordan Fertilizer Industries Company, the Arab Potash Company, the Jordan Petroleum Refinery Company, and the Jordan Cement Factories Company. The second tier consisted of Small and Medium-Sized enterprises (SMEs) that produced consumer products for the domestic market. The government protected the domestic industry through high tariffs and import embargos, as well as market entry restrictions and licensing requirements.[4]

During the 1950s and 1960s, Jordan’s GDP grew by 8-9%[5]. Agriculture played a major role in the economy in terms of value added. However, most of the growth was achieved in construction and infrastructure, as a result of the refugee inflow. On the other hand, manufacturing lagged far behind despite government’s efforts. The domestic industry proved unable to satisfy consumer demand. Therefore, demand for imports of goods and services soared. This dynamic, coupled with the lack of export orientation of the economy, created a trade deficit problem that still characterizes Jordan. In 1972, exports of goods and services represented 34% of imports[6]. Nevertheless, Jordan was able to cope with the negative trade balance thanks to the inflow of remittances from Jordanians working abroad, as well as to official development assistance (ODA) from the Arab oil rich countries strengthening the current account

- Growth History of Jordan Part VI: the Second Phase of Struggling Economic Reforms (1992-1999)

- Growth History of Jordan Part V: Economic Reforms Clash Against the Gulf War (1989-1991)

- Growth History of Jordan Part IV: Facing Reality with the End of Free Lunches (1985-1989)

- Growth History of Jordan Part III: Sustaining Growth at the Expenses of Public Imbalances (1974-1984)

- Growth History of Jordan Part II: the First Growth Interlude (1967-1973)

[1] Chatelard, Geraldine. “Jordan: A Refugee Heaven”. Migration Policy Institute. August 2010.

[2] Kanaan, Taher H. and Kardoosh, Marwan A. “The story of Economic Growth in Jordan: 1950-2000”. Amman: October 2002 (unpublished).

[3] Piro, Timothy J. “The Political Economy of Market Reform in Jordan” , ”The State and the Economy in Historical Perspective”. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 1998.

[4] Ibidem. Kanaan, op. cit. The Library of Congress. “Jordan Country Profile”. September 2006.

[5] Kanaan, op. cit.

[6] Alissa, Sufyan. “Rethinking Economic Reform in Jordan: Confronting Socioeconomic Realities”. Carnegie Endowment. July 31, 2007